Hundreds of tonnes more plutonium has been separated from spent nuclear power reactor fuel than has been recycled in fresh mixed-oxide (MOX) nuclear reactor fuel. The result is global civil stockpiles of separated plutonium that are sufficient for tens of thousands of nuclear weapons, raising severe diplomatic and security concerns. On 25 October 2018, the VCDNP and the Nuclear Proliferation Prevention Project (NPPP) at the University of Texas at Austin held a seminar on this topic, entitled “Plutonium Stockpiles: Causes and Solutions.”

The seminar featured the work of Dr. Alan J. Kuperman, Founding Coordinator of the NPPP, and Miles Pomper, Senior Fellow at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS). Dr. Kuperman presented his new book, “Plutonium for Energy? Explaining the Global Decline of MOX,” which documents how the buildup of civil plutonium has resulted from the economic, safety and security challenges of fabricating and using MOX fuel. Mr. Pomper presented the findings of an ongoing research project that explores current and past institutional, legal and political measures to minimize plutonium stockpiles and offers recommendations for future action. The research findings will be published on the CNS website by the end of the year.

The problem with MOX

Dr. Kuperman began the seminar by identifying a range of indicators that demonstrate that MOX fuel is in a state of global decline. There are only seven countries worldwide that have engaged in the commercial MOX fuel market for thermal reactors and he noted that five of those countries have already decided to phase out their MOX programmes. According to Dr. Kuperman, this is primarily due to the fact that plutonium has three inherent and interrelated disadvantages as an energy resource: safety, security and cost.

Plutonium emits alpha radiation. Although alpha radiation is easily blocked by materials like paper or human skin, plutonium is in oxide form when manufacturing MOX fuel, making it easy to inhale, in which case it can be extremely toxic. In order to mitigate any health risks to workers or the public, facilities require costly equipment and procedures. These significant costs are sometimes exacerbated when facility operators’ attempts to cut costs backfire. This, in turn, has an extremely negative effect on the public’s disposition towards the use of plutonium, which is in general already negative due to plutonium’s weapons potential. Because of these problems, utilities have had a difficult time using MOX fuel in an economically feasible or politically popular manner.

In addition to plutonium’s inherent problems, Dr. Kuperman’s research has found that the way in which MOX fuel is handled raises security risks. For example, fresh MOX stored at power plants is not guarded differently than spent uranium fuel that has been irradiated in a power reactor. While both of these materials contain plutonium that could potentially be separated, spent uranium fuel is extremely radioactive, which constitutes a natural deterrent to theft. Fresh MOX fuel, on the other hand, has no such natural deterrent and the plutonium in MOX fuel could be chemically separated with relative ease.

All of these challenges have created a situation where some countries reprocess their fuel but much of the separated plutonium is not being recycled. So, it is simply building up in stockpiles and there is not yet a clear answer as to what should be done with it. Dr. Kuperman concluded his portion of the presentation by recommending that all countries that are recycling plutonium in fresh fuel, or are considering doing so, should reconsider that decision, citing the cost, safety and proliferation concerns of plutonium-based fuel.

What to do about it?

Mr. Pomper began his presentation by observing that, while much work has been done to ameliorate the threat that excess high enriched uranium poses, relatively little has been done with regard to plutonium. The recommendations that Mr. Pomper presented can be thought of in three categories: (1) limit existing reprocessing programmes and their risks; (2) limit the risk of existing civil plutonium stocks; and (3) discourage new reprocessing programmes.

Mr. Pomper provided two recommendations for limiting reprocessing programmes that are already in operation. First, in the view of Mr. Pomper, countries like Japan that are planning to introduce a MOX fuel cycle should not do so unless nuclear operators clearly demand such fuel. Secondly, France, which is planning to scale back the percentage of its electricity generated from nuclear power should similarly scale back its MOX programme.

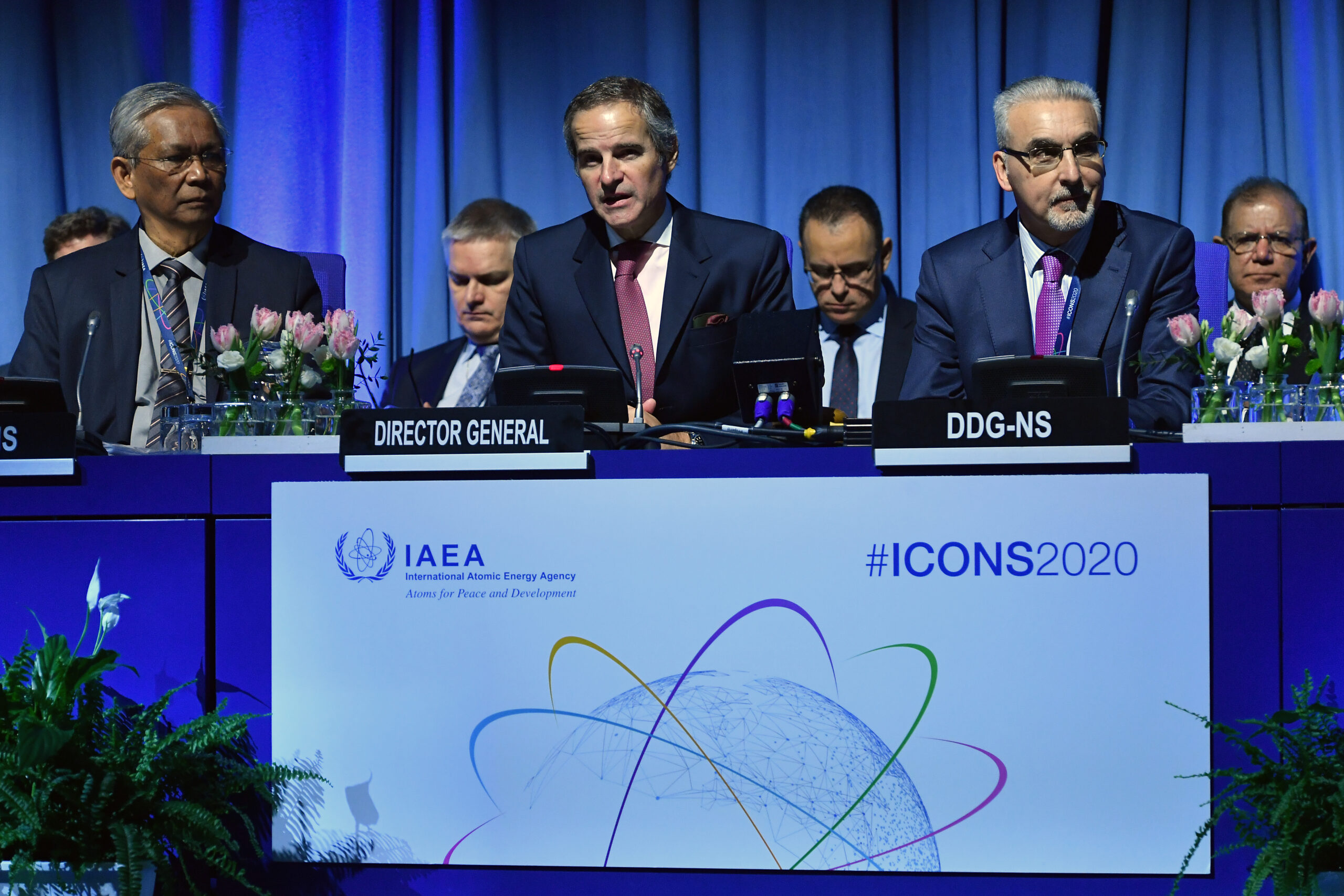

Limiting the risk of existing civil stocks is a somewhat more complicated issue, said Mr. Pomper, and thus requires a number of political and technical steps. Politically, a new multi-state forum should be established to develop strategies for the permanent disposition of civil plutonium. The international community should also reexamine concepts around plutonium storage, including using the regulatory authority of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to safeguard all such materials and place them under international supervision, as provided for in the IAEA Statute, Article XII.A.5.

Technically, there are short-term steps and long-term steps that can be taken. In the short term, the number of sites with separated plutonium and the number of transport movements should be minimised. In the long term, MOX fuel rods could be stored with regular spent fuel, taking advantage of the natural theft deterrent that the radioactivity of the spent fuel provides. The international community could also cooperate on development of the so-called dilute-and-dispose method of plutonium disposition for long-term, sustainable solutions.

Finally, discouraging new MOX programmes will require a number of steps, including constraining reprocessing technology in both legal and illegal channels, as well as actively promoting dry cask storage methods like the dilute-and-dispose method as alternatives to reprocessing. Additionally, proliferation resistance and safeguards-by-design principles should be built into any new facilities related to plutonium processing and use.

The seminar concluded with questions and comments from the audience, including an exchange of competing views on what the energy utility of plutonium could be and different ways in which the international community could engage in controlling civil plutonium stockpiles.